Like so many, I shudder to think about the choice our nation has made.

Like so many, I worry about how this decision will affect my family and the families of so many people I know and I worry especially for those who can so easily become victims of bigotry, exclusion and persecution.

Like so many, I fear for the changes that may/will be brought by a Supreme Court which seeks to reverse advances that have been made in so many critical areas.

Like so many, I am absolutely devastated that so many in our nation either embraced or ignored statements of division and rhetoric of hatred.

But all of us must move on from here, continuing to be the most just, compassionate individuals that we can possibly be and pray that our new leadership will live up to the true ideals of our nation. Like so many of us, I have spent tonight tossing and turning and not seeing how that last part could possibly happen. But, we must hope that that will be the case and must find a way to continue to hope and work for a better future.

I pray for wisdom for our new leaders and for peace, justice and God’s blessing for this, still the greatest nation in the world.

Author: administrator

Some Final Thoughts

This past Erev Shabbat, I posed a question to those gathered for services. I asked them to envision what our country would look like, what it would be like, this coming Erev Shabbat. What would our mood as a nation be? What would our future look like?

I imagined what Noah would have felt had he had the opportunity to envision what the world would be like after the flood. Perhaps he was too busy taking care of all of the animals to have even considered that question, perhaps he spent sleepless nights worrying about what lay ahead. But, one way or the other, if he did think about the future, it would have been difficult for him to conceive of what awaited him. No one had ever been there before.

In some ways, I feel that this is comparable to our situation today. There is so much that we don’t know about where we will be once this election is over. For some of us, we are just absorbing ourselves in our daily lives and awaiting the results. For others, we have, in fact had those sleepless nights, the kind that cause anxiety and fear as we consider the future.

I am supporting Hillary Clinton and hoping that she wins this election. I have been careful not to say this from the pulpit directly although I am sure that I didn’t have to say it directly for people to understand it. It is consistent with political opinions that I have expressed in the past and my grave concern about the horrendous rhetoric and the isolationist, extremist positions offered by Donald Trump leave me no other reasonable choice. I admire Secretary Clinton and believe she is intelligent, compassionate and truly dedicated to improving the lives of individuals and bettering our nation in general, yet I am not completely enamored with her as a candidate and am concerned about many of the criticisms that have been raised and some of her actions. But, to me, this is a clear cut choice.

But, regardless of who wins the election, my question with which I began this posting remains.

Will the results of the election be accepted by the losing candidate? What will happen to the anger that has been raised throughout this election process? Can we recapture the bipartisan cooperative spirit which is so necessary to any kind of progress facing the issues of our time? Will our nation still live up to its stated principles as a nation of justice and compassion.

That last value is of paramount importance. As you know and can read elsewhere in this site, I spoke on Yom Kippur about the importance of compassion and I spoke in depth about how this election has been so lacking in compassion.

This isn’t the first mean-spirited election and it surely won’t be the last. But, the depths that have been reached and, even more importantly, the apparent willingness of so many to overlook divisive, insulting, hate-filled, immature and childish statements is so deeply troubling. Where will this lead us once the election has been decided?

The time has come for all of us to do two things: first, vote if you haven’t done so already and secondly, each and every one of us must commit ourselves to leading our nation away from the destructive nature of this campaign and move towards a brighter future.

When we see a rainbow, we are obligated to say a blessing in the spirit of the covenant that God promised at the end of the story of Noah: Blessed are You O Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who remembers the covenant, is faithful to His covenant and fulfills that which His promised.

Our nation is built on a covenant of justice, compassion and equality.

May we remember it, be faithful to it and fulfill the promise that our nation has always represented.

My Etrog

At the synagogue, we usually bring in about 50 etrogim between those congregants have ordered and those that we buy for the synagogue and the religious school. Most years, I am in the office when the etrogim arrive and often can open a few boxes looking for an extra special one.

This year, the first box I opened contained a surprise. Here it is

I fell in love with this etrog. I have never seen one like it. It looked so different and- quite frankly- it looked like it needed a good home. As I said the bracha over the lulav and etrog, used it for hallel and for the hoshanot over the past two days, I really developed a real attachment to this rather unique looking fruit.

I can’t help but draw a comparison and I hope no one is offended. I mean it with great respect.

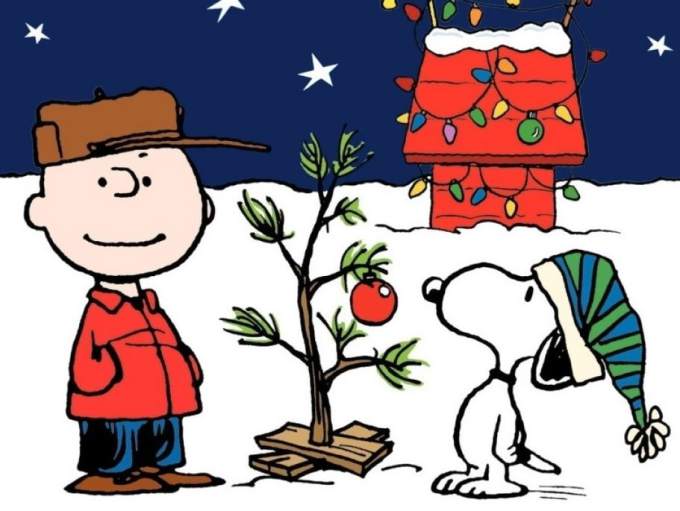

It reminded me of Charlie Brown’s Christmas Tree

The etrog needed me.

The etrog needed me.

To my eyes, it is as the Torah says: the fruit of a beautiful tree.

May we continue to enjoy a beautiful holiday of Sukkot.

Kol Nidre Sermon 2016

Every Friday morning, at the time of the Penitential Prayers, the Rabbi of Nemirov would vanish.

He was nowhere to be seen-neither in the synagogue nor in the two Houses of Study nor at a minyan. And he was certainly not at home. His door stood open; whoever wished could go in and out; no one would steal from the rabbi. But not a living creature was within.

Where could the rabbi be? Where should he be? In heaven, no doubt.

That’s what the people thought.

So begins one of the most beloved short stories in all of Jewish tradition, If Not Higher. Written around the turn of the last century by the author I.L. Peretz, the story has charmed and inspired readers and listeners through the years and for good reason.

I assume many of you know the story. For those who don’t, I am about to ruin it by sharing the ending. But, there is much more to the story than the ending so you will find copies of the story on the table outside the synagogue. You don’t have to put aside too much time, as it is very short.

So, the disciples of the rabbi of Nemirov think he goes to heaven on the Fridays during Elul when the penitential prayers, the Selichot prayers, are said, because, after all, the only thing that could be more important than being with the community is pleading directly to the Kadosh Baruch Hu for their health and prosperity.

But, a skeptic, referred to in the story only as a “Litvak” doubts that the rabbi goes to heaven so he secretly follows him, lying under the rabbi’s bed at night and following him the next morning. He finds that, in fact, the rabbi changes into peasant clothing, and chops wood bringing it to a small cold cabin in which a frail, elderly woman lives alone. He places the wood in the stove, lights the fire, tells her she can pay him later and leaves to change back to his clothing, arriving at the shul just before Shabbat.

So, now when the disciples say that the rabbi ascends to heaven, the Litvak, now a disciple himself, adds quietly: oyb nisht noch hecher, “if not higher”.

Tonight, on the holiest night of the year, in the spirit of this beautiful story, I want to address on one concept, one quality, one human attribute which is one of the most important treasures we possess: the ability to show compassion.

I fervently believe that the most important principle of Jewish belief is the absolute conviction that we can turn this world into heaven, into the garden of Eden. In fact, we can, despite all of our woes and despite all of our disappointment, reach even higher than heaven; but only if we live lives of compassion.

There have been many books written on compassion in recent years and I can’t possibly do justice to the subject tonight. I know I can only skim the surface of what is a much deeper and more complex issue than I will present this evening. Yet we all must begin somewhere and taking time on this holiest of holy days to speak about the subject of compassion is an expression of how indispensable this value is to our lives.

And I know of what I speak.

Over my years as a congregation rabbi, I have learned how deeply compassion matters in the rabbinate. I have learned how compassion or lack thereof and the perception that we are or are not compassionate at any given moment can solidify or completely undermine a relationship with a congregant. Learning this, sometimes the hard way, has been an essential part of my growth in my profession. Neither I, nor any of us is perfect. Each of us, no matter who we are and what we do, must work daily, hourly, to develop further the power of compassion within our souls and learn how sincerely demonstrating compassion is absolutely critical in our relationship with others.

Alan Morinis, the inspiration behind the contemporary revival of Mussar, a Jewish path towards ethical and meaningful living, notes that “the moral precepts of Judaism demand that we be compassionate to every soul”. He defines compassion as “a deep emotional feeling arising out of identification with the other that seeks a concrete expression”.

There are two key elements of that statement. The second is found in the words “concrete expression”. Compassion can not be just a feeling, it must be expressed through action to be meaningful. We must be willing to chop the wood and light the fire.

But, the other key element of the statement is found in the word “identification”.

In one of the most powerful statements in the Torah, we are told that we must not oppress the stranger because “you know the soul of the stranger since you were strangers in the land of Egypt”. According to the Torah, our history of being slaves obligates us to sincerely care for those who are enslaved or who are strangers.

But, this raises a question. If we hadn’t been slaves, if we hadn’t been strangers, if we couldn’t identify based on our own personal or in this case historical experience, would we still be obligated to show compassion to the stranger? And the answer must be yes. There can be no double standard.

While knowing the soul of the stranger might make us more empathetic, it does not excuse those without that experience from acting with compassion. As Alan Morinis teachers, it is about “identification with the other”. We can and must identify with another person simply because he or she is, like us, a human being.

Compassion is not dependent on completely understanding and identifying with the situation another person finds herself in. It means cutting through all of the defense mechanisms we have built that prevent us from deeply listening to and sincerely connecting with others and seeing in another person a human soul, a kindred spirit.

For example, we may not know how it feels to face a particular illness or to endure a difficult financial hardship or to be alone in a new community without friends or family. We may not have experienced the stress that honest and well-meaning police and other law enforcement professionals face and we may not be able to directly identify with Americans of color for whom merely walking down a street or driving a car can mean taking a serious risk. But that can not and must not prevent us from being compassionate and acting to support to those who are faced with those situations. It may make it more difficult but that is no excuse.

Compassion is not sympathy and it most certainly is not pity. Compassion demands that we meet another person face-to-face and eye to eye, as equal human beings, to seek to better understand what another faces as she goes through daily life. Compassion demands that we show respect for another individual as an equal creation of God, deserving of that respect and sincere concern.

In her book entitled: “Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life” Karen Armstrong writes about the charter for compassion which you can read about at charterforcompassion.com. These are statements of commitment to caring for others which many institutions, including the city of Ann Arbor, have signed on to. On the website, which has some wonderful resources on the subject, you will find the simple but powerful words: “We believe that all human beings are born with the capacity for compassion and that it must be cultivated for human beings to survive and thrive.”

This quotation reflects what actually inspired me to give this sermon, one I’ve been thinking about ever since we started using the Sim Shalom siddur some 20 years ago. Every Shabbat morning, we read in our prayer for peace: “Compassionate God, bless the leaders of all nations with the power of compassion”. I can’t tell you how much I dislike that sentence. God has already given all human beings the power of compassion. We don’t have to pray for it. We just have to use it. We are all born with the capacity for compassion.

Both Alan Morinis and Karen Armstrong and my friend and colleague Rabbi Amy Eilberg in her book: “From Enemy to Friend” note that the Hebrew term for compassion- rachamim- shares its linguistic root with the word rechem which means “womb”.

To me, the connection of the word rachamim to rechem means that the ability to be compassionate is part of our very being from the beginning.

In her book, Armstrong notes a theory which I understand has been refuted by many scientists. But I still like it, so it doesn’t matter to me whether you hear it as fact or myth. It is still powerful.

She says that in the “deepest recess of their minds, men and women are indeed ruthlessly selfish. The egotism is rooted in the “old brain” which was bequeathed to us by the reptiles that struggled out of the primal slime some 500 million years ago.” She writes that these creatures were motivated by what are referred to as the “four fs”: feeding, fighting, fleeing and reproduction. She continues: “But over the millennia, human beings also evolved a new brain, the neocortex, home of the reasoning powers that enable us to reflect on the world and on ourselves and to stand back from these instinctive, primitive passions.”

I find this idea to be so deeply meaningful if only as midrash. It is reflected in our Jewish tradition of yetzer ha-tov and yetzer ha-ra, the good inclination and the evil inclination which in at least one classic rabbinic text is represented, not as good vs. evil, but as the self-centered vs. the altruistic and compassionate inclinations. These two tendencies struggle for dominance in our minds and actions. This concept teaches that a part of us is hard wired to be compassionate and that we only need allow it to take precedence over the self-serving parts of our soul.

Compassion is so important in so many arenas of life, most notably in our relationships with one another. But, let me share some thoughts first on the issue in the public arena.

Where is the compassion in our nation? Why, during this election season, are words of kindness and concern and empathy and sympathy not universally expressed? Why, even given differences in our perspectives on policy, are we so often hearing words which degrade and demean other human beings with no compassion and simple kindness?

We see this in the discussion relating to refugees or those in this nation illegally and yes, there must be limits to compassion when it comes to public policy. We have to understand that self-preservation is critical. But, our policies and our priorities as communities and as a nation need to be rooted in respecting individuals and accepting and honoring the basic humanity of another man and woman, whomever and wherever they are, no matter what they look like and, I can not believe that I have to say this, how much they weigh. For they are us. And this is what America must stand for.

And it is what our community must stand for and I am so proud of the efforts of our Jewish Family Services regarding refugees in our community. You will hear more about this and volunteer opportunities tomorrow morning.

Now, I should be point out that Karen Armstrong ends her 12 step program with a chapter called: “Love your Enemies”. I’m really not there. We need to have enough concern for ourselves and our needs to protect ourselves and our families.

But, we would do well to remember the words of the classic rabbinic text, Avot deRabbi Natan which is the basis of the title of Rabbi Eilberg’s book: “Who is a hero, one who turns an enemy into a friend”. It is not prudent to show boundless compassion for those who intend to hurt us but, seeking out ways to better understand another individual and to perform carefully chosen acts of compassion may in fact turn an enemy into a friend and that I have seen happen in my own professional life.

That is why I am so distraught over those who have given up the dream of an end to the Israel/Palestinian conflict and refused to even consider the possibility that there are many Palestinians who are just as frustrated and sick over the continued conflict as Israelis are and who have been so deeply harmed by the past 50 years of occupation. And that is true no matter to whom one ascribes the blame for the suffering of the Palestinian people.

A group of Beth Israel congregants has been meeting monthly for over a year with Jewish and Palestinian members of the group Zeitouna, to learn from each other and share thoughts and fears and hopes with each other. It has been such an uplifting and inspiring experience and I believe strongly that there is still hope. Without endangering our love of Israel and Israel’s needs for security, a relationship based on mutual compassion is still a possibility.

Compassion is a critical piece in Jewish law as well. Our sages repeatedly taught that we must act lifnim mishurat hadin beyond the letter of the law to show compassion for another.

And, there are times when even the law itself fades in importance to compassion. Let me give you an example. We are commanded not to lie. But, a midrash comments on the story in Genesis about Abraham and Sarah in a way which is very enlightening. In the Torah after Sarah says to God: “how can I have a child as my husband is old?”, God relates the statement to Abraham saying that Sarah said: how can I have child seeing that I, Sarah, am old God doesn’t mention what Sarah said about Abraham’s old age. The midrash says that God is teaching us that one can lie for the sake of peace within the home. One can tell a falsehood if the intent is to be compassionate.

Then there is the lovely rabbinic story about the rabbi who is approached by a poor woman. She has just slaughtered a chicken and found its lungs discolored, which might make the chicken tref. She shows the lung to the rabbi and asks him if the chicken is kosher. Before he answers, the rabbi must ask himself one question: can she afford to buy another chicken?

Compassion is more critical than the law.

A few years ago, our Conservative movement radically changed its approach to same sex relationships. It was too long in coming but our rabbis finally found a legal justification for formally recognizing such relationships and same sex marriage within Jewish law. But, whatever resolution their legal investigation brought them, I believe that most rabbis entered into the halachic process with a desire to change the law. That desire was rooted in compassion; not pity, not patronizing attitudes, but in the recognition that the human instinct to love another person is so basic and so foundational that we could no longer turn our backs on what clearly is true love. For so many of us, and I include myself, learning to move past the defenses we had set up to truly look into the eyes of couples who so clearly love each other made all the difference in our attitudes.

And, I believe that our Conservative movement needs to use that same compassionate spirit to allow rabbis to do what we can’t do now and what we could do without violating Jewish law. I believe that Conservative rabbis should be given permission to officiate at a wedding ceremony for an interfaith couple should we choose to do so. If a couple approaches a rabbi to officiate at their wedding because they know and trust the rabbi or because they find Jewish tradition meaningful, we need, within certain guidelines, to say “yes”. I would not seek to make this a traditionally halachic, Jewish legal ceremony as that would unnecessarily compromise Jewish law. But, we could easily develop a spiritual ceremony outside of the law. For the good of our movement and our people, we need, as rabbis, to be part of that couple’s life at that critical moment.

But it is more than pragmatism. It would be an expression of compassion, of validation of the feelings of a couple in love and an opportunity to bring more spiritual meaning to their relationship and to show them that we sincerely mean our words of welcome.

I will not officiate at such a ceremony unless and until I am given permission to do so by our Rabbinical Assembly. But, I hope that day comes soon.

But, to return to the subject at hand, compassion is critical not just in public policy but in our actions towards one another.

Last year, on the first night of Rosh Hashana, I asked you to commit to one new Jewish activity over the year. Many of you talked to me about what you chose to do.

This year, I want to ask you to do something different.

This year, I want to ask you to find one new way each month to express compassion in the year just begun.

There are so many possibilities. We can truly listen to someone in need and hold their hands or hug them tightly. We can perform acts of tzedakah for their own sake and with a willing attitude. We can, as Rabbi Eilberg expresses beautifully in her book, demonstrate compassion by having more patience with the person who drives slowly or cuts us off or searches for the proper credit card while standing ahead of us in line at the store. By the way, my family will tell you that that is where I have to start.

And, we can teach our children, even more sincerely and urgently than we already do, to care for others, to reach out a hand to a friend, to stand up for them when they are bullied or excluded or shamed.

There are so many possibilities. We must constantly search for ways to express compassion in all phases of our lives.

But, as we do, let us remember three additional things:

First, let us learn to freely accept compassion from others. Too often, we think we can get by on our own or we raise the bar of our expectations of others to the point where we reject well-meaning acts of compassion because they didn’t respond exactly or as quickly as we might like. Let us judge others’ actions lichaf zechut, with the benefit of the doubt and accept the kindness of friends and strangers without judgment.

Then, let us learn to be compassionate to ourselves. Let us do what we must do to take care of ourselves, to recognize that we are important too and that in order to do for others, we must be compassionate with ourselves and give ourselves the benefit of the doubt and the respect we seek to give others. Our tradition would demand of us that we practice self-compassion. If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

I’ll preface the third and final point with a story. One erev Shabbat, many years ago, I read If Not Higher to a group of 12 year olds at Camp Ramah in New England. I asked them: “Why do you think the rabbi of Nemirov performed his act of compassion in secret? Why didn’t he tell his community where he was going and what he was doing?”

I assumed the kids would recognize the importance of humility when performing an act of compassion. “Do it secretly and don’t take credit for it”.

But, no one answered my question until one of the campers whom I later found out was the son of a rabbi, hesitatingly raised his hand and said, and I swear this is true; “Maybe she wasn’t a member of the congregation and the rabbi was afraid the congregation board would be angry for spending his time with someone who wasn’t a member”

I am proud of everything this synagogue does here in this building and outside of it to act with compassion for members and non-members alike. I am proud of our willingness and readiness, at all levels of the congregation, to be there at all times for those in need.

But, it is not enough. We must try even harder. Each of us, each of us in our own lives must find more and more ways to bring the spirit of compassion out of our souls and into our world and while I can’t be critical of the rabbi of Nemirov, as I understand his humility and his desire for anonymity, the third point is that it really is OK if others know we act compassionately. It’s OK to be a visible role model for compassion. In that way, we teach others.

All the things that we do here are meaningful only if they inspire us to try to make this world or at least a little corner of it like heaven, if not higher.

So go, be good, do good things, show compassion, light a fire and warm one corner of the world.

Shana Tova.

Dayenu: Rosh Hashana 5777

SERMON FOR FIRST DAY OF ROSH HASHANA 5777

DAYENU: A TEXT STUDY

Although the times might seem to demand it, I have decided not to dedicate a High Holy Day sermon to address the Presidential election.

I made this decision for three reasons and each of them can be summed up with one Hebrew word which you all know: Dayenu. It’s enough.

First, there has been so much press coverage, so much analysis and commentary that by now, I assume you’re saying: “Dayenu”, it’s enough. I hope you have made your wise decision for whom to vote and I certainly hope you do vote. I hope you have come to shul today to consider spiritual matters and to contemplate where you are in life as we begin this new year.

Secondly, you really don’t need a sermon. If you are still uncertain about for whom to vote or about how important this election is, just go back and re-read the prayer for the United States which we heard a few minutes ago. It expresses beautifully our ideals, values and principles as a nation of equality, respect, kindness, justice, appropriate humility and compassion.

Read the prayer. Dayenu. That should be enough.

Finally, both I and Rabbi Blumenthal have addressed political issues from the bima on Shabbat morning many times this past year. We have spoken out and will continue to speak out against words which incite hatred and racial division and against proposed policies which reflect an America which would discriminate against immigrants and Muslims and which do not reflect our values as Jews and as Americans. Many of these sermons were posted on facebook or on our Beth Israel website and some are on my blog as well. Dayenu. It’s enough from the bima.

So, today I’m not going to speak any more about politics. Instead, I am going to do what rabbis are supposed to do. I am going to teach Torah.

I love to teach Torah any time and especially at moments like this when I have the opportunity to expose everyone in the congregation to Torah study including those you who do not regularly participate in our study programs. Hopefully, some of you will be so taken by this text study that you will find your way to one of our various study groups over the year.

I made the decision a few months ago to teach Torah on Rosh Hashana but it took some time for me to decide which text to teach. And here, I’ll remind you that Torah, in this context, can mean any text from Jewish tradition, not just from the five books.

Here were my criteria for choosing a text to teach:

First, I wanted to choose a text that you were likely to be familiar with and one which carries with it positive memories and associations.

Second, the text must contain varied practical and philosophical lessons that can be appreciated by a diverse congregation of individuals who come with vastly different expectations and needs.

Finally, if at all possible, the text must be one which you wouldn’t think merited serious consideration. Finding surprising lessons in unexpected places is a big part of the magic of Torah study.

Those are my criteria and, after some consideration, I made my choice and text is in the envelopes you have in front of you so I will ask those at the end of the rows to open up the envelopes and pass the papers down to those in your row and as you do, we can all start to sing:

Eelu Eelu Hotzianu, hotzianu memitrayim, hotzianu memitzrayim, dayenu.

I have never sung Dayenu with 800 people before. It sounds good, doesn’t it?

We just have to invite more people to the Seder.

By the way, this isn’t the only tune to Dayenu. There are others. My good friend San Slomovits wrote one for a cd of new Seder songs he and his brother Laz produced a few years back. I was honored to work on that project with San and I’ll give you a brief sample of his tune a bit later.

But, for now, let’s begin with the b’racha for Torah study remembering that study in our tradition is also a form of worship and praise.

The first question to consider with Dayenu is where it fits in the Seder.

Dayenu is the last text in the Maggid, the storytelling section of the Seder. The Mishna teaches: matchil biginut u’msayaym bisehvach, we begin with the sad part of the story and end with praise. So, if we consider the Mishna’s teaching, Dayenu, coming at the end of the storytelling, is the ultimate song of Exodus celebration. Dayenu lists 15 separate acts that we praise God for as part of the process of redemption.

And, for each of these 15 acts, we say Dayenu! It would have been enough for us. By the way, if you get bored and count the “Dayenus”, don’t worry that there are only 14. The first verse mentions two acts making a total of 15 and that number is critical as you will see.

Now, the obvious problem and the first Dayenu question: Would it really have been enough for us had God brought us into the desert and not brought us across the sea or fed us food? How could that be “enough”?

The most common answer to this question is that Dayenu means that each of these would have been a sufficient reason for us to praise God. Each one, in and of itself, would have been proof of God’s power.

Let’s think about that for a moment and consider it in the context of our own lives.

Can we ever truly say Dayenu? Do we ever really feel like we have enough to be grateful for and don’t seek any more blessings in our lives?

Most people would justifiably say: “No”. It is natural that we should not be satisfied and should want more and more good in our lives.

But Dayenu teaches us that we can and should look at our lives as made up of many specific, individual reasons to be grateful. We may not have everything we want and in some situations in life, it is difficult to muster up gratitude at all. But, it is important, each day, to ask ourselves: “What are we grateful for?”

We should seek to find something in life for which we can express gratitude every day and say that that piece alone is enough to celebrate the gift of life that God has given us. And, we should be sure to express gratitude not just to God but to the people around us who make our lives what they are. Don’t delay. Do it today.

After reading Dayenu, we might feel intimidated by the author’s effusive praise. But, remember, it was easy for him to say Dayenu about the acts of the Exodus because he was looking in retrospect and he knew that there was a happy ending to the story. In retrospect, after everything has turned out right, it’s easy to rationalize everything and truly appreciate everything that came before. But it is harder in the midst of our lives to express complete gratitude when we don’t know what the future holds. Still, living in the moment and finding the strength to express gratitude adds so much to our lives.

Let me demonstrate that. The list of miracles in Dayenu appears in another place in the traditional Haggada, right after our Dayenu.

These are the same but just in a list without the word Dayenu. It all seems so sterile, so drab compared to our song. You can’t even try to sing this. Without the expression of gratitude and praise, it is so much less satisfying.

When we express gratitude, when we recognize significant events in our lives as worthy of thanks, we add poetry and melody to our lives.

Now, when I read this other section, the one without the shout of Dayenu, I get the impression that the author prefers to see the Exodus as a total experience rather than breaking it down to individual pieces.

But, I think Dayenu’s approach is more reflective of the way we look at life.

We try to envision our life as a packaged unit but it’s so difficult. In the midst of life, we usually see events and judge each one as they are happening. Occasionally, on Rosh Hashana or perhaps on one of those dreaded but so, so welcome “special birthdays”, we take the opportunity to look back, to take stock and see events neatly fitting together. But, much more often, we see our lives as steps along a path, hopefully with some direction but in the midst of life, we are more likely focused on the step we’re on rather than seeing the entire stairway.

I began this morning by singing a tune that everyone knows and I mentioned San Slomovits. When San began to work on a tune for Dayenu, I made him promise that he would make his tune better than the familiar one in one critical way.

Our familiar tune is lacking because it leaves out the most important line of Dayenu. I refer to the introductory line. Without this line, the song is much less meaningful.

Kamah ma’alot tovot l’makom aleynu. How many acts of kindness God has performed for us! (This translation comes from the Rabbinical Assembly Haggada.)

I begged San to include it and he did, writing the following

Kamah, Kamah Ma’lot, Tovot Limakom Alyenu…

Why is this first line so important? It is critical because it clearly was the inspiration for the entire song. The key word is Ma’alot. Ma’alot translated here as “acts of kindness” literally means “steps”.

The author of Dayenu took the 15 events of the Exodus and introduced them with the word: “steps”. What you need to know and this is proof that there is often more going on in Jewish texts than meets the eye, is that the number 15 was not arbitrary.

If you look in the book of Psalms, you will find 15 psalms that begin with the expression: Shir Ha’ma’lot, a song of steps. And, you should know that there was a certain stairway leading up to the Temple in Jerusalem which had, of course, 15 steps.

So, the author of Dayenu looked at this idea of 15 steps of the Exodus and related it to the 15 steps on the way up to the Temple itself which as you can see by the last sentence is the last of the steps of redemption as the author imagines it. The 15 acts of Dayenu correspond to the 15 “step psalms” and the 15 steps up to the final place of redemption.

Now, let’s think of our lives.

Think about the past year as a stairway. Did you climb? Did you move closer to your goals? Even if you do not know where your life is leading in the grandest sense, did you perceive some kind of a movement upward and can you picture that stairway, even with its twists and turns and its uneven steps, still moving you upward?

Not every year will provide that sense of satisfaction but we must do all we can to climb higher each year, pausing occasionally to catch our breath but always looking towards a great goal while expressing gratitude for that which we have.

Rosh Hashana is like a landing between floors, a time to look back and most certainly to look ahead as we continue to climb towards our ultimate goal.

May we all reach a bit higher this year. May we go l’ayla ul’ayla, higher and higher on our path, expressing praise and gratitude for each step, big or small.

Now, let’s look more deeply into the theology of Dayenu.

I believe that when looked at from a theological perspective, this beloved song is potentially one of the most dangerous documents that our people have ever produced. I love to sing Dayenu and will continue to sing it loudly. But, it scares me terribly.

Let me explain this by referencing a recently published book entitled: “Putting God Second” by Rabbi Donniel Hartman. In this book, the author makes a strong and so deeply needed case for the primacy of ethics in religious life, noting that our interpersonal behaviors are more important than any rituals we may perform or any faith we display. The ultimate purpose of religion is to lead to an ethical life.

I could not agree more.

But, I am particularly interested this morning in Rabbi Hartman’s formulation of what he calls the two “autoimmune diseases of religion”: aspects of religion which are self-destructive, preventing people from acting according to the moral principles and ethical values which ought to be the entire reason we engage in religion in the first place.

He calls these two diseases: God-intoxication and God-manipulation.

And Dayenu, our beloved song, is evidence of both.

Hartman defines God-intoxication as a religious viewpoint which “distracts religion’s adherents from their tradition’s core moral truths” and “consume our vision that we see nothing other than God.”

Think of Noah who ignored the plight of his fellow human beings in his zeal to do God’s will. Think of Abraham who was willing to sacrifice his son to prove his faith.

Religion has to be about more than responding to God or recounting what God has done or can do for us. We have to focus on what we can do as human beings with God and our tradition’s guidance.

So, how do we deal with Dayenu which is only about what God has done, phrase after phrase, step after step, about what God did for our ancestors and no mention of any courageous stands or acts of commitment taken by the Israelites during the Exodus? This seems like the dreaded God-intoxication and in fact is just that.

We can answer this by saying that the Exodus is an exception to the danger of God-intoxication. The Exodus is considered by our tradition to be the paradigm of God’s involvement in our world. But, once the Exodus was complete and the Torah was given, it is clear that God retreated, at least to some extent, in the background when it comes to our lives on earth to allow us to find our own paths with free will. So, we can talk in these terms at the Seder about the great experience of the past.

But it is dangerous when we do it about our lives.

From a theological standpoint, Dayenu, when left alone, is misguided. Our lives can not be a litany of what God has done for us. That takes away our responsibility as human beings.

Perhaps that is why Dayenu is written in the third person while so many other of our prayers address God directly in the second person. Perhaps that is why it is written in the past tense even though we are supposed to be reliving the Exodus at the Seder and acting as if it is happening right at our tables.

Dayenu is about what a third person God did for our ancestors, not how you, God, relate to us today.

Being intoxicated with God to the point of denying the fact that we hold the key to the quality of our lives is dangerous. This Dayenu model is not Judaism as we consider it today.

The other “auto-immune disease” that Hartman describes is God-manipulation. He teaches that “the great paradigm of God-manipulation is the myth of chosenness and the ways in which it is used to serve the self-interests of the anointed to the exclusion of all others”.

Wow.

How is that for a quotation on Rosh Hashana?

By the way, I think he’s right.

Our world is, sadly, full of “religious” people who see their faith as the only true path or, worse, who strive to advance their own faith through the oppression or destruction of the “other”. Seeing this is enough to cause anyone with any sense at all to question the value of organized religion altogether.

And so, Dayenu presents a potential problem.

Dayenu tells an honored and foundational story in which God saved our people and cemented our relationship to the exclusion of others.

You know, it’s OK to have such a story. Many, many religions do.

But, to believe that God continues to act for our people at the exclusion of others and to use our “chosenness” as an excuse to justify selfish actions which harm others and to invoke the Divine to continue to favor is, I believe, a hillul hashem, a desecration of God’s name. This sense that “God is on my side” whether reflected in selfish behavior and superior attitudes or, so much worse, in horrendous, unspeakable violence is horribly offensive. The idea that God judges by virtue of heredity rather than by moral behavior is truly a disease that can undermine any good religion can bring to this world.

Just like with God-intoxication, this attitude must be limited to the experience of the Exodus. But, if we take the attitude of Dayenu into our day and assume that God is fighting our battles in opposition to the rest of the world just because we are who are, we are guilty of what Hartman calls God-manipulation and we are moving away from what should be our goal as human beings.

I believe our rabbis knew this and that is why our liturgy refers to two different times in which God interacted directly with our world and why we make Rosh Hashana such an important holiday, as important in many ways as Pesach. This is the anniversary of creation and that concept of divine creation is as dear to our people and critical to our faith as it the redemption of the Exodus.

While I hope, God willing, to give many more High Holy Day sermons in my rabbinic career, another Rosh Hashana reminds me that there are more in my past than in my future. Lately, I’ve been thinking quite a bit about my favorite High Holy Day sermons, some of which will appear in the book that I’ve been working on for years and is now being prepared for publication.

One of the sermons that I did not include in the book was one I gave several years ago. I spoke about creation and stressed that Judaism implores us to believe in Intelligent Design, in a universe created consciously and with a purpose.

Of course I don’t believe in Adam and Eve. I believe in the Big Bang Theory and in Evolution. But, I also deeply believe that God orchestrated that creation to produce a world of thinking, creating and potentially good-doing human beings who could, if they put their minds to it, work together despite their differences to create paradise.

I believe in a divine creation not only because it gives us a sense that we are here for a purpose but also because it unites each person in the world as part of God. As important as the Exodus and Sinai are to our people, it is creation which celebrates the basic humanness of each individual In the world and I believe that if we and other people of faith would spend as much time talking about creation as we do about the specific moments in time that God established our unique faith covenants, we might find religion to be more a source for peace rather than conflict in the world.

Dayenu celebrates the Exodus and the importance of the giving of Torah and the land of Israel. They are absolutely critical to us as Jews. But they are not enough.

For each of us, our greatest expression of gratitude to God should be for the fact that against extraordinary odds, each one of us just happened to win the lottery when that one sperm and that one egg met. I believe a list of the acts we should thank God for, the ma’alot tovot, should begin with the two moments of creation, that of the world and that of ourselves.

That is what we should be grateful for. In and of themselves, they are cause for a big, heartfelt, loud, …no not Dayenu, because it is not enough. Our creation is not enough. We must make the most of the gift of creation we’ve been given. That is cause for a big, loud…Halleluyah.

We need the Exodus story. We need to remember and honor and cherish that which makes us unique and embrace the rituals and traditions which bring meaning to our lives as Jews. Those traditions can help to heal, to repair our world.

But, honoring the God of creation helps us to find commonality with all in the world and helps us to recognize the humanity of others, including to give just one example, immigrants or refugees whom we must view as fellow human beings not as threats to our sheltered lives. Thinking about creation should help us to build bridges, not walls.

So that is it: quite a bit to learn from a song that many of us first sang when we were very, very young.

The lessons are the importance of gratitude, the steps in our lives, keeping God in perspective while doing our job as human beings and seeking to unite with other people in the world rather than making religion only a divisive force. Talk about these ideas at lunch today and remember them six months from now when you sit at your Seder table and celebrate our unique covenant with God.

And, by the way, there is one more lesson of Dayenu and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention it. For the sake of those in the world who do not have enough and for the sake of our planet which must support our children and grandchildren and God willing, untold numbers of generations to follow and for the sake of our tradition which can only function in a world that works, maybe the most important message of Dayenu is that we learn to say: “it’s enough” when we know we can along with less.

But, one thing that we can never get along with less of and one thing that we should never say Dayenu about is the greatest gift we have as a people: the gift of wisdom and insight, the gift of learning and commandment, the gift of Torah.

Let us pledge to make this year of Torah learning and the life of commitment it inspires us to live as we graciously and gratefully move, God willing, to the next landing.

Three Serious Jokes for Rosh Hashana

This morning, I shared three short jokes with the congregation. Each has an important message as we enter into the High Holy Days.

Joke #1 A man visits his friend in Jerusalem. He realizes his watch has stopped so he asks the man what time it is. The man goes to his balcony, looks up at the sun and tells his friend that it is 3:00 p.m. The friend is surprised that he can tell the time from the sun and his host tells him that he has learned to do so and doesn’t even own a watch or a clock.

So, his friend asks him: what do you do at night? He says: “I use my shofar, come back tonight and you’ll understand”.

So the friend comes back in the middle of the night and the man goes out to his balcony and blows the shofar.

Immediately, three people can be heard screaming: “It’s 3 a.m. and you’re blowing the shofar?”

The shofar is, in fact, a clock. It reminds us of the passage of time. One year has passed since we heard it last and we are one year closer to the time when we will no longer be able to change our lives for the better.

When the shofar is blown, realize it is keeping time.

Joke #2 A man brings his car to his mechanic and says simply: “My brakes don’t work well. Can you fix my horn?”

Too often, when we recognize faults in ourselves, we deal with them by expecting others to alter their behavior to account for these failings. Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur remind us that we all have faults, that we all have been less than we can be and that if we want to change our lives, it is up to us to make the change. To warn others about our failings and expect they will make life easier for us by changing their expectations of us is wrong. If something doesn’t work correctly, we should change it.

Finally, joke #3 A woman is frantically looking for a parking space as she is late for a very important meeting. In her desperation she calls out to God: “Dear God, if you find me a parking space quickly, I’ll give $10,000 to tzedakah.”

She turns the corner just as a truck is pulling out of a space right in front of the building she needs to go to.

She says; “That’s OK, God, I found one.”

No one can guarantee that you will experience a spiritual awakening over the holidays. No one can promise you that you will hear God’s voice or that you will be moved to the depths of your soul by the sound of the Shofar or the melodies of a prayer or words spoken from the bima.

But, if it happens, if you truly are moved deeply by something you experience, if you truly feel like you have been touched by something beyond yourself or deep within yourself that you haven’t felt before, don’t make excuses.It is a wonderful gift. Accept it, celebrate it and let it light your way in the New Year.

Shana Tova u’mituka to all: a good sweet year of health and peace.

Shimon Peres Z”L

Although there is so much more to say, I want to post an immediate reaction to the death of Shimon Peres Z”L

Shimon Peres was a man of principles. He was completely dedicated to his nation and sought to insure that Israel always lived by its principles and its values. He was dedicated to seeing an end to conflict and sought to make true peace.

I had the opportunity to hear him speak on more than one occasion and was impressed as all were with his wisdom and his strength.

But, there was one other thing about Shimon Peres that I always thought whenever I saw him. He just happened to look almost exactly like our next door neighbor when I was a kid.

That may not seem important and, of course it isn’t. But it is important in a symbolic way.

When I think of Shimon Peres, I immediately think of Yitzchak Rabin Z”L and of that glorious day so full of potential and promise when they stood on the White House Lawn with Yassir Arafat and President Clinton to sign the Oslo Accords. To see Rabin and Peres standing there gave me not only a sense of pride but a sense of identification. These two leaders (and in another era, I would include Golda Meir Z”L in this same thought) represented the possibility of an emotional, deep connection for Jews throughout the world and Israel. They looked like our neighbors. They were our association with the State..

Policies aside, I don’t have that feeling about Israel’s current leadership and that is a loss for all of us who yearn for deep connections with Israel.

Leadership not only means standing “above” the people but being one of the people, being a person people can look to with trust and in partnership. To me, that is the essence of leadership and one which Shimon Peres emulated throughout his life.

May his memory be for a blessing.

Officers and Judges

SERMON FOR PARASHAT SHOFTIM 5776

OFFICERS AND JUDGES

As we approach the High Holy Days, it is our responsibility to engage in teshuva, repentance- to redirect our thoughts and our actions and consider how we are going to make this new year different from those that have passed.

And, it is our responsibility as rabbis to try to find ways to shed light on the issue of teshuva, to find new texts or ideas which can provide new perspectives on the process of repentance.

Today, I want to share with you a beautiful commentary on the first verse in Parashat Shoftim. Then, I want to provide a twist on this commentary which I hope will provide an interesting thought relating to teshuva.

Our Torah portion begins with the words: Shoftim V’Shotrim teetayn licha bichal shiarecha asher ado—nai elohecha notayn licha.

Judges and officers shalt thou make thee in all thy gates, which the LORD gives you.

Clearly, this is a vital and foundational commandment for a community. The obligation to build a community based on justice, with appropriate safeguards is one of the requirements for the sacred community envisioned in the Torah. But there is more of interest in this verse.

The Torah is clearly talking about 2 different types of positions when it identifies shoftim and shotrim. Shoftim are judges but what are Shotrim? I have read many commentaries with many different ideas but for this morning, I am going to approach this from a bit of an anachronistic perspective and base my definition of shotrim, on the contemporary Hebrew word with the same root; mishtara, meaning “police”. “

Shotrim is to be understood as those who protect the community and Shoftim are those that decide what is just and what is unjust.

Now let’s look at the second part of the verse because it is somewhat odd: “at the gates that God will give you”. While I understand the implication: that God will give the people the land in which the gates will appear, it is a difficult phrase and begs for an interpretation. How does God give us gates?

A commentary cited in the 17th century commentary called Shnei Luchot Habrit by Rabbi Issac Horowitz provides an answer.

The commentary begins by quoting the early mystical Jewish work, Sefer Yetzirah, which teaches that there are 7 gates to the soul: the two ears, the two eyes, the two nostrils and the mouth.

Whatever the original meaning of this text, the commentary goes on to say that these shearim, these gates, take the external impressions of the world and bring them in to our lives. Thus, says this commentary, we must place shoftim v’shotrim before each of the gates that God has given us, that God has created for us. It explains that it is our obligation to protect ourselves from that which comes in to our gates; namely, that we should allow no negative impressions to come in through these gates, that the ears would not hear bad words, the eyes not see evil and so on.

I love the idea behind that commentary. It gives a beautiful meaning to the phrase: “the gates that God has given you” and reminds us to be steadfast against being influenced by evil of all kind.

But, I have to add a bit of a twist to the commentary. The lesson that is taught: that we should protect negatives from coming into our gates is really only about shotrim, those who protect rather than shoftim, those who judge. When he says no negative impressions come in, he is talking about our being shotrim, guarding the gates.

However, the truth is that we can not completely control what comes in through our gates. Over the year to come, just like in past years, no matter how we may try to avoid them, we will hear negative things, we will see inappropriate actions. We will experience all of these.

That is why we must focus also on being shoftim, on being judges. While we can’t completely control that which comes in, we can judge what is worthy of us.

So, let us look at the first verse of the Torah portion and consider the following. God has given us gates, gates which can be open to let in that which we must hear, the cries and needs of others, the words of wisdom shared by honored teachers, the inspiration we receive from those around us.

In truth, we need to be shotrim, we need to guard ourselves from hearing and seeing things which are not worthy of God’s image within us. We need to put ourselves in situations in which we can be more sure that we are hearing and experiencing positive, constructive words and actions.

But, let’s not fool ourselves. We live in a real world and we can not isolate ourselves from all of the negatives in the world. That is why that we need also to be shoftim, to judge that which has come into our gates and make sure to distinguish between that which is positive and that which is destructive.

May we find ways to surround ourselves with goodness this year knowing we won’t entirely accomplish that. So, when negative realities get by our shotrim, may we always be ready to judge what will lead our lives and our world to a better place.

Gene Wilder

It’s time, unfortunately, for another blog posting in memory of a well known individual. This time, Gene Wilder.

So many roles in so many very, very funny movies: Blazing Saddles, Young Frankenstein just to name two. But, my favorite role of his was as Avram, the inept young rabbi from Poland sent to San Francisco (as far away as they could send him) in The Frisco Kid.

I haven’t seen the movie in a while and I’m not sure that as a whole it has stood the test of time but the first time I saw it (in Israel, by the way), I thought it was one of the funniest movies I had ever seen. His interactions with Harrison Ford, waiting for the sun to set so Shabbat could be over and they could continue their journey, calling the Amish farmer: “lantsman” and the whole (admittedly non PC) scene with the Native Americans were priceless.

But my favorite scene comes towards the end when Avram feels he isn’t qualified to be a rabbi any more because of some of the things he has done on his way out west. So, carefully carrying the Torah scroll he has brought all the way from Poland, the one which he has saved and has saved him, he approaches the house of the leader of the Jewish community in San Francisco and pretends to be someone else.

He tells the man’s daughter that he met the rabbi who couldn’t come but gave it to him to give to her father.

She asks what it is and in a great accent, Avram says: “I don’t know, I think it’s some kind of Torah”.

There are funnier moments in that movie and in his other roles but that line absolutely cracked me up and every time I think of it, I smile.

There is a mystery to that line, a significance that I can’t put my finger on but I just love it and all it can possibly mean.

And, I have to confess.

Sometimes, when we take the Torah from the ark to carry it around the congregation and to read the weekly portion, I catch myself looking and saying: “I don’t know, it’s some kind of Torah”.

It sums up how I feel about our most sacred possession which is so hard to describe.

Thank you Avram.

Rest in peace, Gene Wilder.

THE POWER OF WORDS

Sermon delivered at Beth Israel Congregation, Shabbat Nachamu, August 20, 2016

I have spoken from the bima recently about the power of words in comments on our Presidential election. After I posted one of my sermons on the issue on Facebook, one of my Facebook friends replied with a quotation by Sigmund Freud which read in part: “Words call forth effects and are the universal means of influencing human beings. Therefore let us not underestimate the use of words”.

Today, I want to speak about another use of words which has been terribly difficult for many of us. These words came in a recent statement of principles issued by the Black Lives Matter movement, whose cause I have spoken about previously from the bima, which included these words: “The US justifies and advances the global war on terror via its alliance with Israel and is complicit in the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people,” It goes on to say: “Israel is an apartheid state with over 50 laws on the books that sanction discrimination against the Palestinian people.”

The Black Lives Matter movement, whether or not one agrees with all of the rhetoric, is raising very significant issues, concerning racial discrimination in law enforcement, in the justice system and resulting mass incarceration of people of color. These issues should be very important to us as Americans and as Jews given our tradition’s absolute commitment to justice as the first priority for building a sacred community.

But, these words hurt and they must be clearly condemned.

I completely and utterly reject the idea that Israel is engaged in genocide. This is a horrible mischaracterization of the situation. I also believe Israel’s policies can not be compared to apartheid in South Africa and reject the comparison.

We can’t ignore these words. They matter. Even if the positions are ancillary to the basic goals of the movement, the leaders felt they were important enough to be mentioned and that is of great concern. These words are hurtful and untrue and, sadly, they do affect how I and many of us will interact with the efforts of this group.

But, our community’s zeal to condemn statements of this kind leads me to a great concern which arises whenever words like these are used about Israel from whatever source.

Too often, we concentrate too much on the words expressed in virulently anti-Israel statements so much so that we allow them to divert our attention from the reality. Granted it is not genocide or apartheid, but Israel’s policies toward the Palestinian people are gravely inconsistent with Jewish values and tradition. They must be radically changed and we as a Jewish community, dedicated as we are to justice, must continue to focus attention on these unjust policies.

No, Israel is not completely to blame. Violent terror and rejectionism is a big piece of the story. But, if we care about justice, if we care about ethics, if we care about doing what is right, we can not let the exaggerated words we hear from others divert us from our responsibility to raise our voices against policies in Israel which are unethical.

We are justified in being uncomfortable with how other groups talk about Israel and Palestine, and that includes the Black Lives Matter movement and the Boycott Divestment and Sanction groups. But, it is our critical responsibility to offer a serious, sincere and meaningful alternative to their language which will show that we are deeply concerned and sincerely committed to applying whatever pressure we can on the Israel government to move in a different direction.

I can’t ignore the language of the Black Lives Matter movement regarding Israel. But, in the end, the language doesn’t change the fact that we and every American need to stand up and speak out and take action against the biases which cause so much pain in the black community. We are one nation and this is our fight too.

And, similarly, as Jews the fight for justice for Palestinians in Israel is our fight too.

I believe that we need to dedicate ourselves to being unmistakably clear that, even as we appropriately care so deeply about Israel’s security and survival and reject extreme language, we too know that the Palestinian people are suffering. We must raise our voices clearly, using different, more accurate but serious and clear language. We must use words which convey our deep frustration and, to use an extreme word of my own, but one which I feel is totally appropriate, our heartbreak, at what we see.